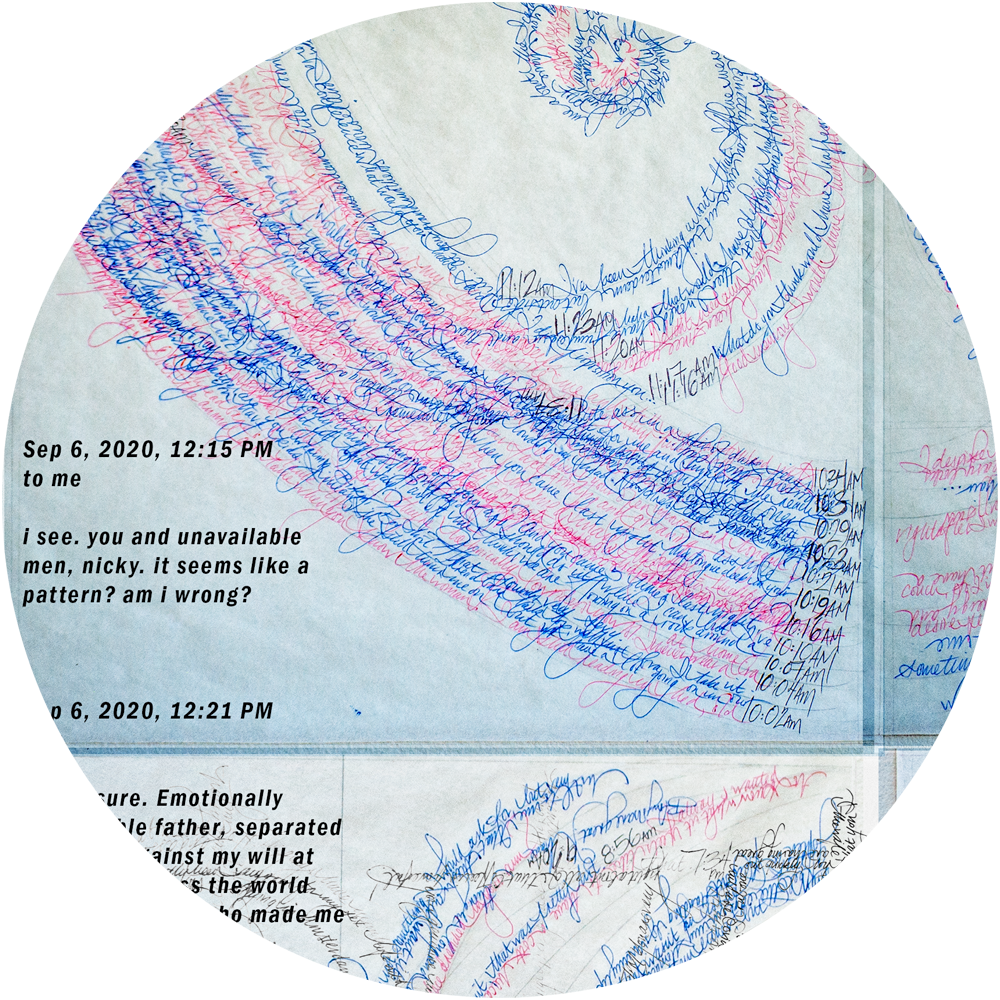

‘That picture of her is the capsule that has exploded into the larger, unbounded picture: so each contains the other, although they are so different...she is the ‘little’ that gets turned into ‘a lot’.’

(Williamson, Loc 2869)

The Transformative Myth

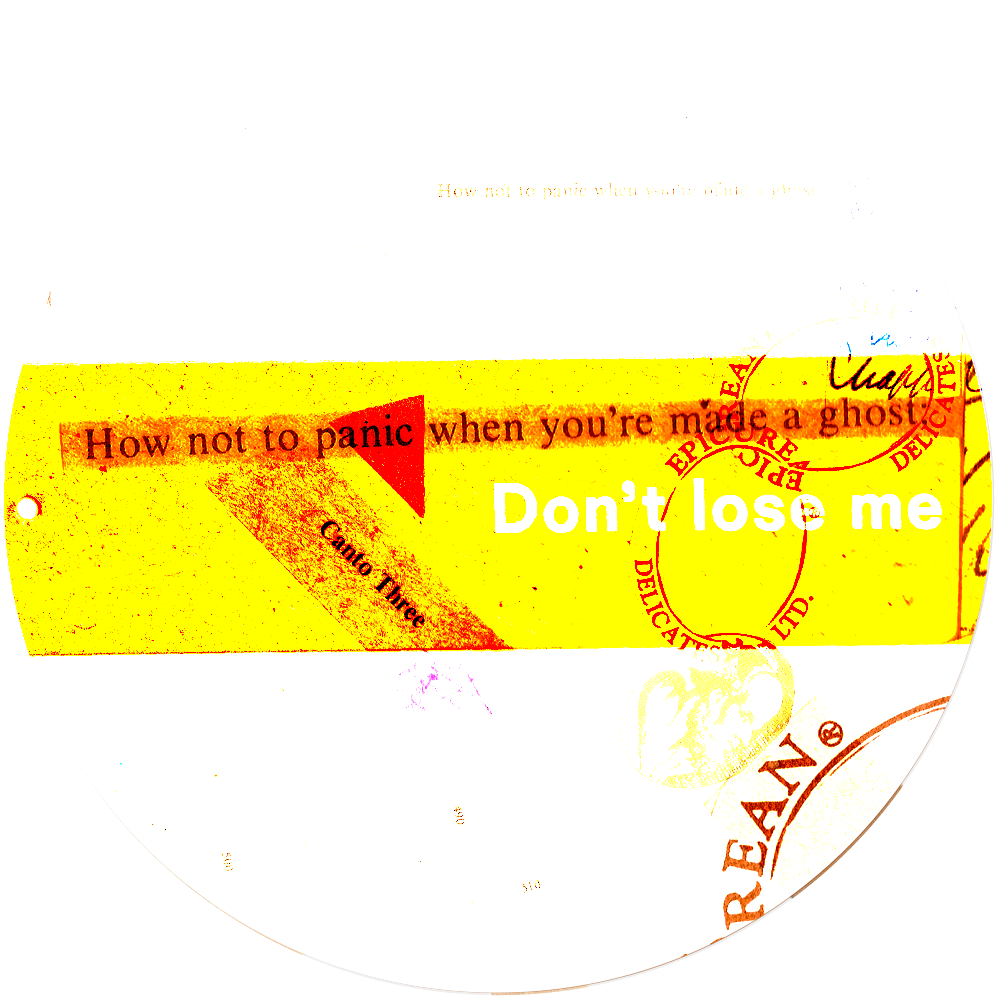

of the Cinderella Pseudo-Environment

‘Find the one everyone is talking about...”

“...the forgetful one who loses her shoes.’

(The Prince’s father on his death bed, Cinderella, 2015)

‘...sometimes it’s really hard to walk in a single woman’s shoes. That’s why we need really special ones now and then to make the walk a little more fun.’

- Carrie, Sex and the City, A Woman's Right to Shoes

“No one sees the world like my Tom.”

“People come to me with their dreams.”

“The poor things drop like flies"

“It is the insertion between man and his environment of a pseudo-environment ... it may be a long time before there is any noticeable break in the texture of the fictitious world.”

(Lippmann, Loc 184)

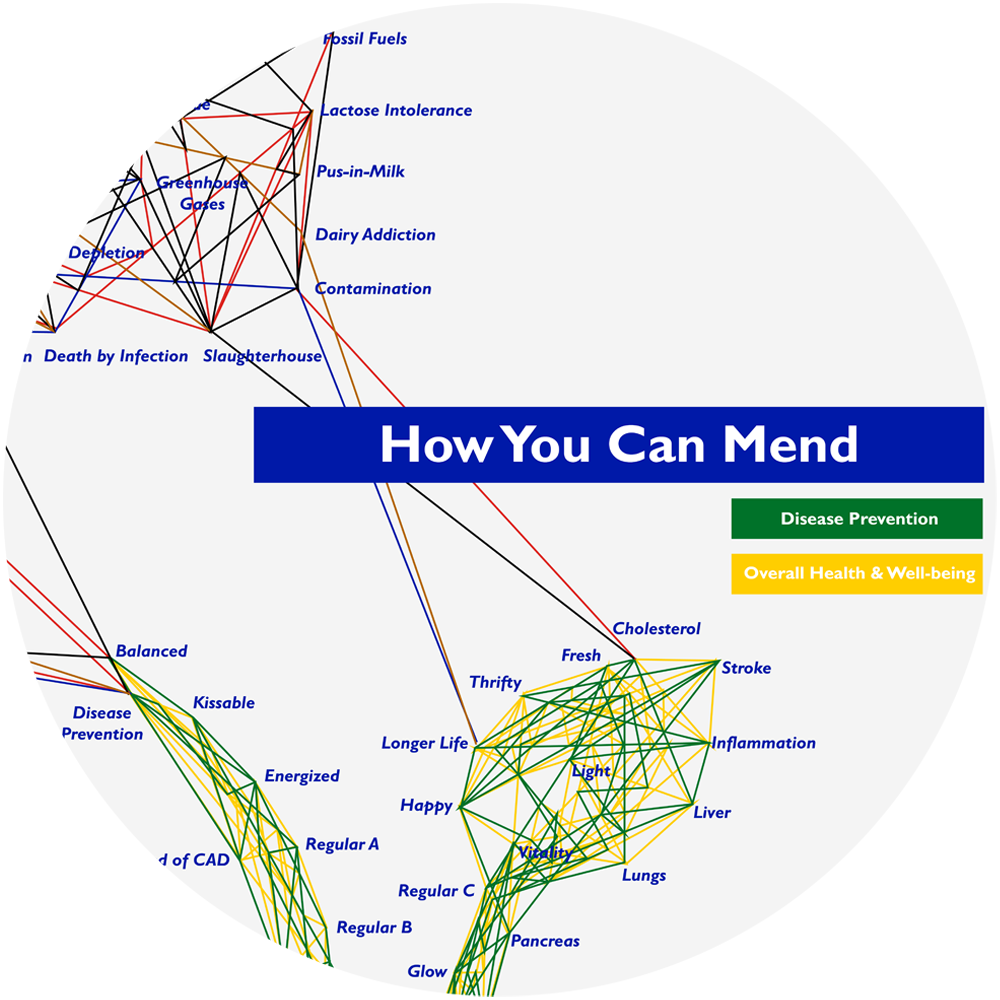

According to Roland Barthes “myth is a semiological system which has the pretension of transcending itself into a factual system” (Barthes, 133)*. Cinderella and recognizable characters from her story (a glass slipper, a blonde woman in a pink or blue dress, working class rodents etc) are “language-objects” of myth, “its total term, or global sign”(Barthes, 114). Walter Lippmann corroborates this notion in his Pulitzer Prize winning classic Public Opinion: “For it is clear enough that under certain conditions men respond as powerfully to fictions as they do to realities, and that in many cases they help to create the very fictions to which they respond.” (Lippmann, Loc 181) He pointed out the “the insertion between man and his environment of a pseudo-environment…” (Lippmann, Loc 184)

The story of Cinderella is co-opted as myth and operates subtly and obviously, to sell a variety of products and lifestyle concepts. The spread titled “…the forgetful one…” is comprised of a few of these brands and its antecedent “find the one…” is made of various depictions of Cinderella in these ads. Her myth is so pervasive that Lippmann’s ‘pseudo-environment’ came as a natural descriptor.

The title spread “Dream Big Princess” depicts the grooming of small girls to be perfect little princesses. My first thought in discovering these images was ‘Why are these little girls posed with men and not little boys representing princes?” The story is of an age appropriate union, afterall.

This is the power of myth. Using this alchemy it becomes socially acceptable to preciously depict a child as a princess bride within a consumer culture that simultaneously frowns upon the sad reality of child brides. The dress transforms her into the much bigger myth, lifting her away from the inappropriate reality in which she is photographed: “Myth can reach everything, corrupt everything, and even the very act of refusing oneself to it. So that the more the language-object resists at first, the greater its final prostitution…” (Barthes, 132).

The pyramid form unifies this research under the symbol of the arcane pre-science of Alchemy. “Alchemy is not the process of making something from nothing; it is the process of increasing and improving that which already exists.” (Hall, Loc 9662) The function of myth in advertising is identical: products are imbued with the power to increase and improve the consumer without having to explain the product’s actual or contextual value. Judith Williamson describes “the ‘Cinderella’ syndrome, the magic of personal transformation” (Williamson, Loc 2878): “So the ‘little’ Jane becomes the ‘cool, beautiful blonde’, who is bigger; thus the small picture leads to the larger one.” (Williamson, Loc 2869) Although she is describing a hair product advert from the 1960s, the description carries, timelessly, easily transposed into the next product.

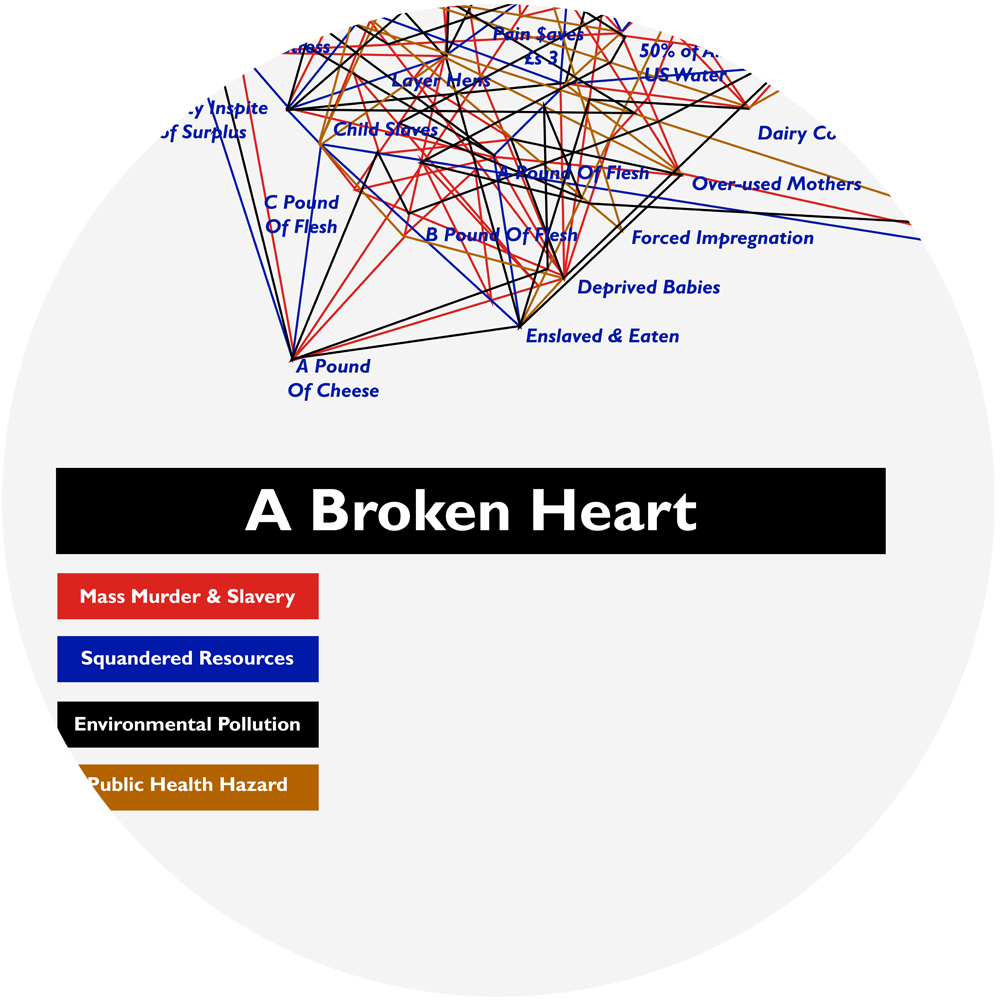

The essay closes with a two page commentary on the often harsh realities of fashion production. Cinderella is aided by cute proletarian animals, innocently endearing in the story. In reality, when a fairy tale is used to sell wares, fashion or otherwise, produced by real people working in exploitative industries for low pay and high profit, the myth reaches the level of corruption.

Burberry is a brand that takes particular care perpetuating the Cinderella myth. It is a luxury brand, distinct from the middle class consumer products that Cinderella is often used to tout. Once Lily James, a distinctly English actor, had featured in Sir Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella, she was selected as Burberry’s spokesmodel. Soon thereafter she featured in Branagh’s Romeo and Juliet on Broadway in London, once again opposite Richard Madden as her prince. Burberry’s existence in the social media environment is sufficient for swift associations to be made using shares, tags and hashtags.

Sara Jessica Parker, who depicted Carrie in Sex and the City, represents an easily recognizable Cinderella story and while never an official spokesmodel, is nonetheless anointed by Burberry with personally monogrammed clothing. The quote I have chosen in her spread is from an episode of Sex in the City titled ‘A Woman’s Right to Shoes’ where Carrie loses her Manolos at a party.

The sky backdrop invokes the lyrics “Just the two of us/building castles in the sky”, as well-known as Cinderella and as far-fetched a concept. Marriage isn’t a promise of perfection and there is no consumer product that will make you kind, special or good. Dreams, hopes and plans are the actual goods being sold using the Cinderella myth to mask the common drudgery that Rush lite milk, Babo kitchen cleaner or a meal at MacDonald’s represents.

*Full bibliography, image and quote references available upon request.